Things Are Not Okay In Rural America

Many, if not most, of our rural communities are in decline, and have been for many years. The simplest explanation for that is that the world has changed. What, exactly, it was that changed to cause a particular place to begin its downward slide may differ, to some degree, from one place to another, but the fact is that most rural places are not well-situated to thrive, or to even survive, in the world of today.

There are all sorts of things one might point to as examples of decline—deteriorating infrastructure, loss of key industries, loss of vital community resources, etc.—and some of these events may be present in one community and not in another. Some things are probably even going well. For instance, lots of small towns, thanks mostly to federal grants, now have new parks and other amenities that they didn’t have years ago, when they were prospering. But there is one factor that almost all struggling, rural communities have in common—they are losing population. No matter what else is going on--no matter if some things are improving, no matter if people want to argue about what else might be going on in a community—it is a simple, unarguable fact that no community can survive a declining population. And it’s not just a pure numbers game. It’s not JUST that the population is going down. It’s who is leaving and who is staying. It’s generally the young people who leave, taking their energy, their passion, their ideas, their ambition and their modern skill sets with them. This leaves behind a population that is older, sicker, more stagnant and less able to adapt to, or to even contemplate, change.

People and distance are the defining characteristics of rural places. There are relatively few people, and those people are, except for small towns scattered here and there, spread out over a large geographical area. Because of this low population density, rural places generally have more limited resources, both financial and social, than more metropolitan areas. People, though, are the most limited resource of all, and because of that, anything that might be done to change the trajectory of rural places must be about people, not just things. A new park, for example, is not going to change the future of a dying town. It might help some, and it will certainly be a positive step. It might improve the quality of life for the citizens, but it’s not going to change that slow downward trend. It’s a real problem that community leaders who are in a position to help lead change and the people who can provide the funding for change generally like to do things and invest in things they can stand in front of and cut a ribbon. Investing in people isn’t as easy or as visible. It’s much more difficult to find the political will, the societal push, or the funding to do the sorts of things that address complex root causes.

How We Got Where We Are

So, how did rural places get in the shape they are in? Most rural places have an inherent structural flaw, and that flaw lies at the very heart of the community. Communities exist for a reason. Nobody was ever walking through the woods on the frontier and just decided to build a town. There was a reason. Very early on, it probably had to do with whether or not a boat could get to it. Most of the oldest towns anywhere are ports, whether they are seaports or riverports. Transportation was, and to a degree, remains key. Maybe a crossroads was a good place to set up a market town where farmers could bring their produce. Maybe the river was a good spot to build a mill. Whatever the reason, all towns start for a reason. Some of those towns grow to become cities, but most of them remain small towns sprinkled around in rural areas and the economies of those towns are focused on that one industry, whether it is a riverport, a railroad junction, a factory, a mine, an agricultural market or whatever. Other businesses crop up, but the mainspring of the economy usually stays centered on a single industry or employer. These “company towns” work, more-or-less, as long as the company remains in profitable operation, but what does a company town do when the company shuts down? What then? This is the situation faced all through rural America. As the global economy has shifted and evolved, often rural places find themselves without any real reason to continue to exist. They try to re-invent themselves and develop new economic engines, but they often lack the resources to do it. Then the people, starting with the youngest and most productive, start to leave and the problem accelerates. This is where many of us are today in rural America.

“The way we’ve always done it” isn’t working, if indeed it ever really did. Some of the strengths that tend to define the character of rural people, such as that independent streak and love of tradition can become obstacles when fundamental changes are the only way to save our communities. We live in a very unfortunate time. There are a few people who are getting what they want by turning the rest of us against one another, at the very time when we most need to be working together. Many of our communities have been in decline for decades. For some of those communities, it is probably too late to turn things around. For others, there is still time, but that time is drawing short. Prosperous communities require something of a “critical mass” of economic and social activity to remain viable, and once they lose it, there is probably no way to get it back. Many of our communities are on that edge. Some have a little more breathing room, but none of us probably have more than a few years, at best, to start to turn things around. We have to start now and we have to recognize that “the way we’ve always done it” is not the way we need to do it. The time for waiting is over. The time for small steps is over. If we want to preserve rural America, with all the good things that come from it, we have to be ready and willing to pursue big, fundamental changes.

Foundations For Change

All those problems aside, rural America remains an essential part of the national fabric. It’s not only the products of the farms, mines and other industries that are rural in nature. It is also the people and the culture that add strength, character and diversity to what remains the American Melting Pot. I grew up in a small town in rural Kentucky, and I’ve always been glad I did. I left after high school, because I couldn’t get the education I wanted or do the type of work I wanted to in my hometown. Having lived in several cities, and having seen and done some things I would never have seen or done had I stayed in my hometown, I’m still glad I grew up there. I think that rural environment contributed a great deal to the person I am today.

There are people who think that rural America is an anachronism and that resources invested in trying to stabilize it and help it remain viable in the modern world are wasted. They think that, aside from the people who have to live in rural places to farm or work in the necessarily rural industries, everyone else should just move to the metropolitan areas where there is much more economic opportunity and many more resources. These people aren’t crazy. They are, in my estimation, wrong, but they aren’t crazy. It would, no doubt, create a more efficient economy to do that, at least for a while. The cost to our society, though, would be catastrophic. I believe, wholeheartedly, in the worth of rural America, culturally, socially and economically, and I want to see it not only survive, but thrive. For the parts of rural America that are still hanging on, it is possible to do what needs to be done to change that downward trajectory. It will be difficult. It will be very difficult. These are not small issues that are facing our communities. We didn’t get in this shape overnight. The steps we will need to take will, likewise, not be small and they will not happen overnight. The good news is that we already know what the steps are. Most of what needs to be done already has been, in bits and pieces, here and there. We don’t have to reinvent the wheel. We just have to apply things that have already worked. Sure, there will be new ideas and things that arise along the way, but we’re not starting from scratch or anything like it.

That, then, leaves the question, “If we already know how to do most of what needs doing to turn things around for rural communities, why are rural communities still in such trouble?” That’s a good question, and I think it has a good answer. That answer is that we haven’t applied all that stuff we know in a way that will allow for the kind of long-term, sustained impact we need. To explain what I mean by that, let’s turn to a military analogy. I like analogies and I use them a lot. If you are a military officer planning an attack, it’s actually fairly simple, on the surface. You are given a mission (an objective). You are given as much information about that objective (number of bad guys in the way, where they most likely are, what their weapons and other supplies are, etc.) as possible. You are then told how many troops and other resources you have at your disposal and when your boss would like things to get done. That’s oversimplified, but not really by very much. You know what force you have at your disposal, and you know where it needs to be applied. A key concept to that is something called “combat power”. Combat power is sort of like horsepower in a race car. The more of it you have, the more likely you are to win, but you have to use it wisely. One way to maximize combat power is to mass your forces, which means take what you have and apply it at a focused point to get the most effect. For instance, If your mission is to take control of a town that is defended by 5000 bad guys, deployed in a circle around the city, and you have 5000 guys of your own, how do you attack? Do you deploy your troops all around the city and attack from all sides? Do you break your formation into 10 groups of 500 and attack from 10 different directions? Both of those are bad plans. The first one won’t work at all. The second one might seem like it’s making progress in 10 different places for a little bit, but that progress is unlikely to last, because it gives the enemy time to redeploy to counter your attacks. No, what you do is MASS YOUR FORCES. You take all (or most) of your power, find the weakest point in the bad guy perimeter and attack that single point with overwhelming force.

What we’ve been doing with our resources up to now is akin to those first two plans. It’s not just for rural issues, either. Those first two plans are pretty much how we approach most of our big problems: we either take our resources and use them in the wrong places or we don’t use enough resources to really change anything. We know, for instance, that improving access to health care lowers costs and leads to healthier people. We know that works. We know many different ways to improve health care access. We also know, for instance, that improving access to safe, stable, affordable, quality housing leads to decreased poverty, better health, better workforce participation and better quality of life for the community. We know lots of ways to do that, too. We know that improved access to affordable childcare leads to more people being able to work as well as children being better prepared to enter kindergarten. We know ways to make that happen. We know that helping people with substance use issues to get to recovery or to reduce the negative consequences of substance use results in people getting back on their feet and rejoining productive society. We know that works. We know how to do it. We know that forming coalitions of community organizations helps to maximize the impact for everyone. It’s been done a million times, and it works, particularly in rural places where resources are more limited. We know all of this stuff and much more. It’s all been done and it all works. The thing is that nobody does it all. That is where we fail to achieve real change. We aren’t massing our forces. When anything at all happens, it’s someone working on their own to do a particular thing. It’s about the issue and not about the people. There is a better way, and I’ll explain what that is.

First, we need another analogy. Let’s say, for instance, that we have a 12 year-old girl who comes into the hospital Emergency Department 8 or 10 times a year with an acute asthma attack. This is fairly easy to treat, so they take care of her attack and send her home, knowing full well that we will be seeing her again in a month or so for the same problem. She’s going to be back, because her home is full of black mold, which exacerbates her asthma. Her home is full of black mold because the pipes under the kitchen sink leak. What this girl needs most to take care of her asthma is a plumber, not a doctor. So, is it leaky pipes that is at the root of her health problems? Would fixing the leaks take care of the situation? Let’s examine the situation a little further. Why are the pipes leaking? Well, the pipes have been leaking because her mom can’t afford to get someone to fix them. Why can’t she afford to get someone to fix them? Because she works two jobs, but they are both low-paying, so that still doesn’t leave enough money to pay a plumber. Why can’t she get a better job? She has no job skills. Why doesn’t she have any job skills? She’s tried a couple of job training programs, but she hasn’t completed either one. Why hasn’t she completed a program? Because she has a substance use disorder (SUD). Why does she have a SUD? Because she got in a car wreck 3 years ago and got addicted to prescription pain medication. What the little girl with the asthma problem actually needs the most, then, to be healthy, isn’t a doctor, or even a plumber. What the little girl needs is substance abuse treatment for her mother. If her mom gets through that, then she can get some job skills, get a job that pays a living wage so she can pay her own plumber to fix the pipe. Then the mold goes away, the asthma attacks stop (mostly), and the little girl and her mother start living a “normal” life and moving toward reaching their potential.

From the outside looking in, this girl has a problem with chronic asthma and the solution is to treat it. In our analogy, that’s what we are doing now. It doesn’t work particularly well, because her asthma is always a problem, getting to a crisis point every month or so. Not even taking into account how badly the asthma is affecting the girl, her long-term health and quality of life, her episodes of treatment are costing $20-30,000 a year. Every year. And between the hospital charging off the cost and the taxpayers paying through Medicaid (if the girl has Medicaid), everybody is paying for it. And will continue to pay for it. A few hundred dollars to pay a plumber to fix the pipes would eliminate most of this particular problem, but there really isn’t a good way for anyone to actually even know about that issue, and if they did know, finding the money to pay the plumber would be difficult, because there aren’t any specific programs to do that. All, or at least most, of our resources are deployed in the wrong places. As a wise proverb says, there comes a time when we need to stop pulling people out of the river and go upstream to find out why they are falling in.

The Role of Health--Not Just Healthcare

And now it’s time for a brief explanation of what are referred to as the Social Determinants of Health (SDH or SDoH). Healthcare is CRAZY expensive. We all know that. One could go on at some length about why that is, but that’s a subject for another time. Let’s just stick with “it’s expensive”. Given that it is so expensive and often inefficient, the entities who pay for most of it, private insurance companies and the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS), which is the federal agency that runs and funds the two large government healthcare programs, along with all sorts of other organizations that have an interest in the healthcare system, have been working for years on ways to make it better and cheaper. The big payers (CMS and the insurance companies) have, for several years, been advancing a number of new healthcare delivery and payment models designed to lower costs while, hopefully, improving outcomes. Again, not to get too far out in the weeds, most of these models are what are called “patient-centered care” or “value-based care”. Healthcare providers are setting up new systems called “Accountable Care Organizations” (ACOs). Perhaps you’ve heard some of those terms. In any event, the idea behind all of those new models is that it is better and cheaper to try to keep people healthy than it is to wait until they get sick and then try to treat that condition. “Waiting until they get sick and trying to treat that” is the system that most of us are familiar with. It is often referred to as “fee for service”. Where providers do what they do and then someone pays them for it.

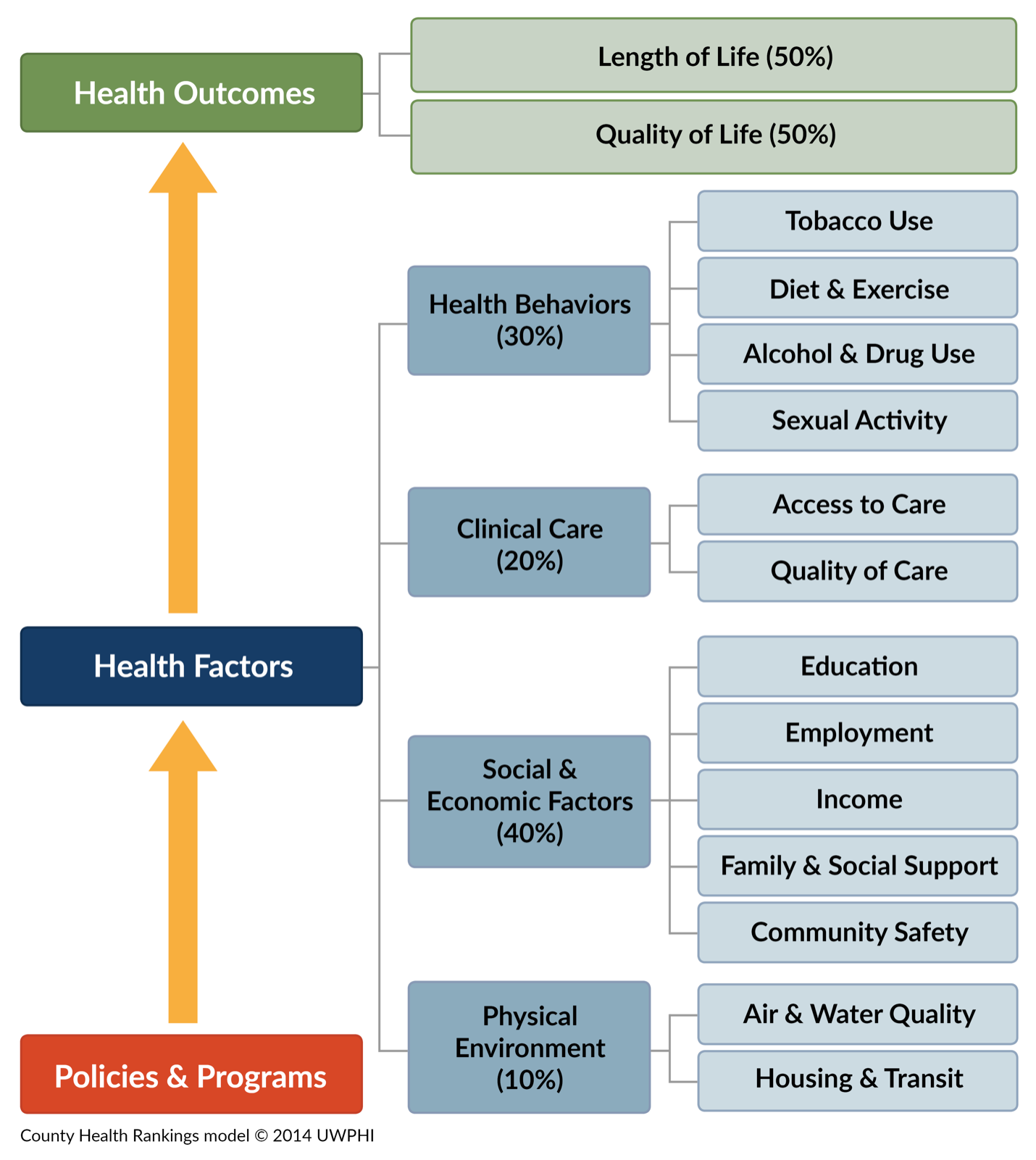

As people have been looking into new ways to move more toward “health” than “healthcare”, a core concept has emerged, which is called “The Social Determinants of Health”. The idea is that most of the factors that impact a person’s health and well-being don’t really have anything to do with what we think of as the traditional healthcare system of doctors and hospitals providing care to sick people. In fact, it’s been determined that as much as 80% of the issues that impact health are SDH. The figure below is a graphical model developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, which is the largest health-focused philanthropic organization in the country. In this model (and other models agree), only 20% of the factors that impact health involve clinical care. The other 80% are how people live, where they live and the behaviors they adopt. All of those factors together determine health outcomes, which come down to lifespan and quality of life. It is probably pretty apparent from this graphic that these factors are all interconnected. What isn’t included in the model is how health outcomes impact the economic viability and prosperity of communities. This connection is particularly strong in rural places where people are a limiting factor.

In relation to the story about the girl with asthma, clinical care is only a very small part of the whole suite of factors that are impacting her health and her future. This all ties together in our model of how to change the future of rural America.

If you look at the graphic, the broad categories of the factors that influence health are in the right-hand column, housing, employment, diet and exercise, access to care, etc. There are already groups working in most communities on all these issues. The problem is that most of the groups working on the issues are focused primarily on those issues. Housing people work on housing, food banks work on food. Maybe someone has put together a coalition to work on homelessness and low-income housing or on access to behavioral health care. As I mentioned, putting together coalitions of stakeholders to address issues is a proven way to make progress, particularly in rural places. Our approach just takes all these ideas that already work and goes a step further. The idea behind our coalition is that that fatal flaw in our approach to these issues, and many of the really big issues of our time, is that we spend all of our energy and all of our resources trying to address the issues we can see and address. We do this with our social programs, we do it with education and we do it with healthcare. When we do this, we are only treating consequences of deeper, more complex issues. We rarely are able to penetrate down to discover what the root causes of issues are. Going back to our story of the girl, we treat the asthma attack, because it’s an emergency. The hospital knows this family in terms of the asthma problem. Social services might know them in regard to food stamps. The school system might know them, primarily due to what all this does to the girl’s ability to be successful in school. Everyone is doing their part, but nobody is looking at the big picture. Nobody is able to find the root causes behind their troubles (the parent’s substance problem), so we just go on treating the symptoms, dealing with the consequences, over and over again, and we likely never get to the foundation and address the issue that causing all the others and holding this mother and her child back from realizing their potential and fully participating in the community in which they live.

Coalition Building and Strategies for Rural Places to Survive and Thrive

The ARCH (Access for Rural Community Health) Community Health Coalition was founded to help find and address these root cause issues for individuals, families, and the community. We exist to help our member organizations and all other community stakeholders take a holistic approach to issues and make the most of the available resources to achieve the best possible outcomes for everyone. Our mission is expansive and our vision is grand, by design. Many would say that we need to find an issue and focus on it. Our position is that it is precisely that tendency to focus on issues and pick a piece of the problem where results can be easily measured in a time frame short enough to satisfy people and funding agencies who want to be able to see results over a year or two funding period. This approach is, we believe, short-sighted. The need to produce visible, quick results keeps change-makers like us from trying to do exactly the type of long-term, complex, often strategic work at both the individual and community levels that needs to be done to achieve real, long-term change. It’s akin to the emphasis on quarterly profits versus long-term growth for corporate reporting. It puts the short-term, often satisfying results ahead of the more difficult, long-term solutions.

We have broken our holistic approach down into 10, still broad and often interrelated, working areas—Housing and Homelessness, Nutrition, Education, Behavioral Health, Substance Use, Healthcare, Issues of Aging, Infrastructure, Childcare and Early Childhood Development, and Community. Some of these areas are only really applicable at the community level, like infrastructure, but most of them can and must be addressed at both the community and individual levels. We will look each of these areas in separate articles to follow. What’s extremely important to remember is that these are broad issues and broad approaches. To really set an agenda for meaningful change, we need to engage with the people who are experiencing the issues. This kind of change only works from the bottom up. Nobody, and certainly not I, can talk to a person or go into a neighborhood or community and say “here’s what your problems are and here’s what you need to do to fix them.” It takes a cooperative effort that includes organizations like the ARCH Coalition and other community stakeholders, like churches; government agencies; business and community leaders; schools; healthcare providers and the people of the community to make things work.