Recall the Hierarchy of Needs and the Social Determinants of Health

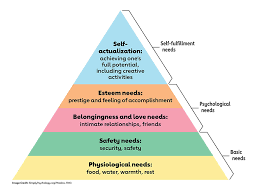

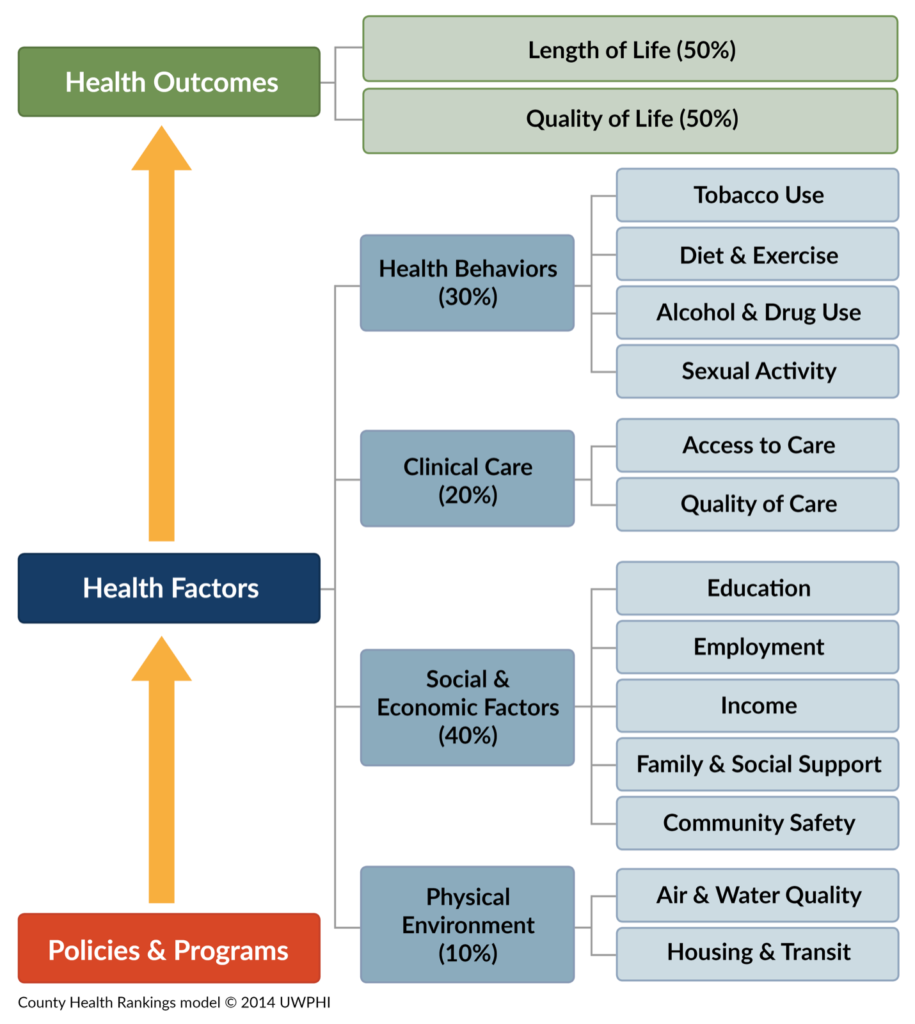

The base of the Maslow pyramid is “Physiological Needs”, which are the things a human body must have in order to survive. These are, obviously, fundamental, and must be satisfied before anything else really becomes possible. These needs (among others that will come up later on) are hard-wired into our brains. The most primitive, oldest parts of our brains are concerned only with acquiring these basic needs. While the SDoH diagram is not a hierarchy like Maslow, and it doesn’t reflect the relative importance of one group of health factors over another in its impact on health, the box at the bottom, Physical Environment” does include some of those same basic needs.

If we wanted to include every factor that contributes to health in these articles, we would probably start now with “Air”, because it is absolutely the most immediately necessary need. We can only go about 3 minutes or so without it before we die. “Water” would be the next, because we can only go a couple of days without that. However, depending on the weather and the overall health of the person in question, “Shelter” would come either just before or just after water. In January, it would be before. In June, after. Either way, housing is a necessity for survival.

Air isn’t something that most of us think much about, because for most of us, it’s not an issue. One of the benefits of living in a rural place is that we don’t have the large-scale air issues that are common to cities. However, if you do live in a city, or you’ve spent much time in one, particularly in the summer, air quality is an issue. Even in some smaller cities, the air quality in the summer can become dangerous for people with respiratory issues, like COPD, emphysema, or asthma. Health agencies will recommend that at-risk people stay indoors. That’s a problem for the homeless. Air quality can also be an issue sometimes, in rural or urban places, based on where you live or work. People living near certain factories or landfills, for instance, might have to breathe in dangerous substances. Certain job sites are hazardous because of chemicals or particulates in the air. Black Lung is an example. It killed and crippled many a coal miner back in the day, and it’s still around, although workplace safety regulations have helped a great deal. That said, air quality isn’t a widespread issue for us, and it’s not something that is threating our communities, so it’s not a priority for us and we won’t go any further into it. I just wanted to make the point that, even out in the country, things most of us don’t give much thought to can be important to some who live right here in our own communities.

Water is sort of like air, as it’s not a widespread issue in western Kentucky, but that’s not to say it isn’t an issue at all. It’s certainly more of an issue to more people than most of us think, particularly if we think of water and sewer together. Water-borne illnesses, like cholera and dysentery, have killed millions of people through the course of human history and are still common and deadly in some parts of the world. Around here, most people are on “city water” and there are rarely issues, unless there is a water main break or something that requires a “boil water” alert. However, there are more than a few people still on well water. Again, that’s rarely an issue, although wells do occasionally get contaminated. Our biggest water issue in this area is for people who don’t have access to running water at all. This is one of the many issues faced by the unsheltered homeless, for whom access to water and sanitation are always an issue. Perhaps a more widespread situation, however, is for people who are not unsheltered, but who are living in places that don’t have running water, either because the plumbing doesn’t work, or they can’t pay the bill. Yes, there are people, and more than a few, living right here among us who do not have running water (or often, electricity, for that matter). Again, I included this paragraph because it’s something that is not particularly rare in our communities that most of us never even think about. Realizing things like this are right here, right now, in our very own community is revelatory. I know it was for me. No running water means more than just no water coming out of the faucet. It means no toilets. No hand washing. No bathing. No clothes washing. Practically no cooking. A simple thing like no running water has a whole host of consequences. I moved to Miami for graduate school in August of 1992, arriving just a few days before Hurricane Andrew hit. It was quite the mess. We didn’t have electricity for about ten days, but we also didn’t have water. Because Miami is so flat, the water pressure is maintained by pumps, not gravity and water towers, like it is here. Even in August in Miami, the modern convenience you miss most isn’t electricity, or even a refrigerator. It’s running water.

I just spent a page writing about the stuff that I’m not really writing this article about because I would like for people to realize that there is WAY more going on around us than we have the slightest clue about. The world you think you are living in and the world a person two streets over is really living in may be wildly different. I know for certain that a lot of what I thought about “the way the world works” for the first 45 years of my life was either just flat-out wrong or woefully incomplete. When we hear about some of these terrible things that are plaguing communities all over, like the opioid epidemic, child malnutrition, old folks dying alone in squalor, veterans sleeping in junked cars and on and on, it’s not happening “there” to “them”. It’s happening “here”, to “us” and we need to be aware of it, because that is the first step to doing something about it.

Anyway, this particular article is actually going to be about housing, because it is also one of those very basic needs that has a profound impact on community health that IS one of our most challenging issues in rural western Kentucky. Our housing issues cover the full spectrum, from homelessness to affordable rental housing to affordable entry-level housing to workforce housing. We have a lot of work to do.

We’ve established that housing is a fundamental, basic need, but why is that? How does it impact individuals, families and communities?

On a physiological level, shelter is necessary because humans are no longer able to survive extremes of cold and heat without help. This is particularly so for the young, the old and the infirm. If you have ever “slept out under the stars” you might have experienced this, unless it was a really warm night. Humans lose body heat by radiating it into the environment. If you are looking up at an open sky, you are essentially radiating body heat into the entire universe. This is why a car parked outside will get frost on the windshield and one parked in a carport won’t. The car outside is losing heat into an unlimited heat sink (the open sky). The car under the carport is mostly only radiating heat into the space under the roof, even if it is otherwise exposed to the open air. If you have ever slept directly on the ground, you’ve experienced much the same thing (again, unless the ground is very warm). The air temperature may be 80 degrees, but your temperature is still 98.6. If you lie directly on the ground, you are going to radiate heat into the Earth, which is another great big heat sink. You WILL get cold. Your body will work hard to generate more heat through metabolism, but there is only so much it can do. Being wet just makes all of those things happen faster. Wind makes it worse. Those are just some of the physiological reasons humans have to have shelter.

Beyond those physical needs, shelter also contributes to a number of psychological and emotional needs that are also part of Maslow’s hierarchy and the SDoH. Being sheltered provides a sense of safety and security, even if it’s not really safe or secure. Every kid who has ever pulled a blanket over their head when they were scared gets this. They know the blanket is no actual protection, but the psychological impact is quite real. We all understand and experience this regularly when we lock our doors at night. We experience it when we feel uneasy and pull our coats more closely around us. We, our families, and our belongings are safe inside, in our minds whether or not it’s true in reality. That safety and security satisfies some of those most pressing demands of our more primitive brains, and until we get it, we will find it very difficult to think beyond it.

Most everyone who will read this has probably been fortunate enough to never have experienced the sort of existential threat posed by being unsheltered or being threatened by it. Most of us have always known where “home” was and has been able to not worry about it being there. I can say that there have been times in my life where it was a real concern to me. I’ve been lucky to have ultimately had options that kept the worst from happening, but I’ve spent some long nights worrying about it. Even for those of us who don’t really have to worry about it, I will bet that there have been times in your lives that the first bill that you paid every month was your rent or mortgage. You may still do it out of habit. Or you may just have it on autopay. Another little personal story—until I was in my 50’s and well past any actual financial insecurity, I never set any of my major monthly expenses up on autopay, because I wanted to always be flexible enough to make sure I could pay the rent and the other “important” bills first, just in case something happened. It’s hard-wired into our brains.

The point I’m making here is that safe housing is “job one” for anyone trying to get through life, and if they don’t have the physical, psychological and emotional stability it provides, expecting them to be able to strive meaningfully toward more advanced goals (getting through substance treatment, taking care of chronic health problems, getting job training, holding a job, etc.) is a fool’s errand. This is why working toward getting homeless people housed matters. It’s why ensuring a sufficient supply of decent, affordable housing and the resources to acquire it is available. It’s not just because it’s the right thing to do. It’s because, if we are to have any reasonable expectation that these people, whom many of us have never really seen as they walk invisibly through the world we both inhabit, will ever be able to “get sober” or “get a job” or any of the other things we think they should do, they will first have to have a place from which to start. Not everyone who gets housed first will succeed in moving ahead, but it’s a fairly safe bet that almost everyone who is left unhoused will stay where they are or fall further behind as the pit they are in grows deeper every night.

There you have my version of the “WHY” for housing. It’s not to build some liberal utopia where everyone has a nice condo whether they pay for it or not, although I personally do think any civilized society should strive to ensure that all of its citizens live with a modicum of security and dignity. No, “why” of housing is that it’s the first, required step on the path for people to become what they, and we, want them to be. I’m no Pollyanna. I’m very well aware that there are a certain number of people out there who are just bad. They are users and haters and takers. But there aren’t really that many, and not a few of those who are that way are so because they know of no other way to be. We are all what life has taught us to be. Some of us were fortunate that we had good people in our lives to teach us how to be good people. We’ve had support. We’ve had role models. We’ve had education that we could actually take advantage of, because we’ve had safety and security. We’ve had opportunity. I used to let those takers occupy space in my head, for the same reasons most of us do. Then I stopped and my life got VASTLY simpler. I stopped because I realized that those people are not my problem. My purpose is to help the people I can help and try to make the world a little bit better, full stop. The takers are not my problem. They are background noise. Most of the world’s religions and philosophies share a few central themes, no matter how different they may seem, otherwise. One of them is some version of “treat everyone the way you want to be treated”. Another is “don’t try to judge others, because you have no idea the road they have traveled”. Here’s a fact--we’ll never be able to help everyone who needs help, but we will be able to help most of the kids, and when they next generation comes along, there will be fewer takers and fewer people who just don’t know how to live life successfully.

And now for the “HOW”, or at least some of the “how”. The ARCH Community Health Coalition has been working for change in the housing arena for some time. A few months back we helped to establish a new local housing development and community revitalization nonprofit. We are very pleased to have this organization in the area and are proud to be partnering with Matchem Community Revitalization in addressing our housing issues.

Housing is, obviously, a big challenge. It’s big because the needs are big. When someone needs a pair of shoes, finding some shoes or the money to buy a pair is not that daunting. Finding a safe, affordable, decent place to live is a bit of a bigger deal. We are thousands of housing units short in our region of western Kentucky, and we are lacking at every level. We’ll go through things one piece at a time, and the order in which we address them here doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with the priority we should place on them. In reality, we are going to have to address all these different aspects of housing at the same time, starting now. They are all necessities, precursors to many of the other things we need to work to change, and we simply don’t have the time to approach things one at a time.

Let’s start with those who lack housing altogether. We lack enough shelter for the homeless, sheltered and unsheltered. By the way, most of the people who are homeless, which basically means people who are living in places that they shouldn’t be, aren’t actually living outside under a blue tarp. Those folks are classified as “unsheltered”. Most homeless people, however, are not unsheltered. Most are couch-surfing with friends or living in their cars or huddling in abandoned buildings. We also have “chronically homeless” people, who have been homeless for extended periods, and “acutely homeless” people who are usually those who have been stably housed but have become suddenly and (hopefully) temporarily homeless due to a relationship change, house fire, getting out of jail, aging out of foster care, release from the hospital after an extended illness, during which they lost their housing, and a million other life events.

When a person (or a family) is living outdoors, Job 1 is getting them indoors. The physical and emotional dangers of being unsheltered are immense and immediate. Shelters are, traditionally, the first resource available. Shelters, by-and-large, provide more than just a roof over the head. They generally provide many other services that most of us take for granted. They usually provide regular meals, usually of decent quality and nutritiousness. They also provide things like a place to do laundry. Proper sanitation. A secure environment where the residents feel relatively safe and where they feel their possessions are reasonably secure. It’s amazing to most of us how valuable things like that are. In places with large, chronically unhoused populations, support organizations often provide accessible lockers so people can secure their things. Portable showers and laundry facilities are greatly appreciated by people who need them. Most of the time, the most requested item from homeless people is just socks. Hard to imagine for most of us. Another thing that most programs support homeless folks does is help to get Driver’s Licenses and ID cards. Again, most of us don’t realize it, but you can’t do hardly anything without a government ID of some sort. You can’t apply for a job. You can’t apply for most benefits. You can’t enter training programs. Can’t open a bank account. Shelters are the front-line resource for people in the greatest need. They are like putting a bandage on a bleeding wound. They are a step on the way to recovery and healing, and without them, some people are going to bleed to death.

We don’t have anywhere near enough shelter capacity in our area. We have one general shelter that serves several counties. There are also a few small shelters dedicated to specific groups, such as women fleeing domestic violence. The general shelter is usually full, or nearly so. There are, currently, no accommodations in this shelter for families or children. It is a “dry” shelter, meaning that people using alcohol or other substances can’t stay there, and the majority of unsheltered homeless people have substance problems. This shelter is also run on a shoestring, because there is no reliable support for it from local sources, like government. It runs mostly off of federal grants and the only reason it has been operating as a full-time shelter for the last few years is because of COVID money. Before COVID, this shelter (which, I remind you, is the only general shelter around) was only open from November to March and, even then, was only open at night. Everyone had to leave each morning, not allowed back until suppertime. When the COVID-related funds are gone, it’s entirely likely that the shelter will have to revert to being a cold-weather, nighttime shelter.

We need more shelter for the chronically unsheltered. We need more capacity for families and minors. Transporting people from nearby counties to the shelter is an expense that can’t be supported. We currently have NO emergency shelter options (aside from the general shelter) for the ACUTELY homeless. Remember, these are folks who have been consistently housed, but who have lost their housing due to some circumstance, like a relationship change, housefire, aging out of foster care, release from the hospital, etc. Where does one go in that situation? How does one keep a job? Take care of children?

We are working on ways to create more capacity for both the chronically and acutely homeless. One way is to create some emergency shelter where the acutely homeless can stay and try to keep their lives on track until they get new housing figured out. Renovating space, like old hotels, is a great mechanism for this. Opening new traditional homeless shelters is also a need. Providing some transitional housing for people ready to move out of the shelter and into more permanent space is another. We have been exploring the development of a “tiny house village” to provide some transitional housing. Finally, there is something called “permanent supportive housing”. These are, basically, traditional apartments for people who need help with physical health, behavioral health or substance issues so they can eventually rise above their circumstances and move into fully independent lives. It’s important to understand that that is ALWAYS the ultimate goal of housing for the homeless. It’s to help get them on the road to being independent, fully functioning members of society. Obviously, not everyone will be able to get there, but dang near none of them will if we don’t pull down some of the barriers in the way.

There are lots of objections to these sorts of programs. The big one is “NIMBY”, which stands for “Not In My Backyard”. Both people who see the merit is these programs and those who don’t often fall prey to “NIMBY-ism”. Nobody wants to live next to a shelter. Or anything else that they prefer not to have close by. I get that. Pretty much everybody gets that. However, everything has to go somewhere, and location is of particular importance for facilities such as these, because proximity to services and accessibility is a key feature for people who don’t have many resources. Moreover, the social issues surrounding places like these are far less than is generally assumed. And it’s simply necessary. We can’t just ignore the issues, because they aren’t going to go away, and I’d much rather take steps to help someone in dire need become someone who isn’t in dire need than to keep paying for the consequences of not doing it. That is the recurring theme to all these articles. Doing these things isn’t just the right thing to do. It’s also the smart thing to do. Poor people are expensive, socially, demographically, and economically. The social expense comes from the damage we face when we do not do what we are able to do to help the least fortunate and weakest among us. It is said that a society is judged by how it treats the least among them. Demographically, we can’t keep leaving people behind. We can’t let entire families just fall by the wayside, generation after generation. We’re rural. We need them to be the best they can become part of a sustainable, productive future. Economically, we need these folks, if they have the ability, doing productive work. Adding to the value of the workforce. Paying taxes. NOT using as many support resources. It’s a win-win.

Beyond things that we can do for the homeless, the next step is that we need to expand availability of affordable housing, both rental and owner-occupied. We are thousands of housing units short of what we need in western Kentucky, and that causes quality and affordability problems from the top to the bottom of the housing spectrum. Part of the problem is obvious—if we don’t have a place for people to live, people can’t come here or stay here. Another part, though, is that the overall lack of housing contributes to a particular lack of affordable housing. The definition of “affordable” in relation to housing is that any family that spends more than 30% of its income on housing (including utilities) is overburdened, impacting the ability to be able to pay for food, transportation, medical care, etc. The median fair market rent for a two-bedroom apartment in Hopkins County is about $700, which is actually much lower than many other parts of the country. It is, however, about 7.5% higher than it was a year ago. If you add about $200 for utilities, a family would need to make about $3000 a month to afford an apartment. A single parent would have to make about $18 an hour in a full-time job to be able to afford the rent.

We don’t have enough affordable housing anywhere in our region. The ARCH/MCR partnership is working toward helping to alleviate this. Part of the reason that we don’t have enough affordable housing is that no one wants to build affordable housing, because it’s too expensive to build and the return on the investment is low. It’s much more profitable to build $300,000 single-family homes in a subdivision. And we need those, too. If we want to expand the availability of good, middle-class jobs, we are going to have to expand the supply of housing for those new middle-class people to live in. However, since developers can make decent money building those houses, they generally will build where there is demand. Building affordable housing is more of a challenge. It’s pretty much impossible to build affordable housing without subsidizing the cost of construction or rehabilitation. There are several mechanisms to do that. The largest player, by far, is the US Department of Housing and Urban Development. HUD, in addition to operating government-owned housing projects and providing direct rental assistance, subsidizes most of the affordable housing development in the country. The US Department of Agriculture also plays a significant role in housing in rural parts of the country.

We’ll not go into the financing process, here. Suffice it to say, it’s complicated. There aren’t many developers who work in affordable housing, so usually it’s some out-of-town company that builds and manages new affordable housing. The downside to that is that much of the revenue that is generated by the housing leaves town, instead of being re-directed into the local housing market. This is why ARCH and MCR are partnering. MCR was set up to act as a local developer, so that we can start working in the affordable housing arena with the objective of building up our communities, not making money. The process is complex, but we have started on the road to developing the affordable housing that we need. Part of it is new construction of multi-family developments. Part of it is rehabilitating existing housing, taking substandard structures and making them whole. Not only do we get more decent housing that way, we also improve the quality of our neighborhoods. Part of it is building new, affordable homes. Part of it will be establishing the financial tools we need to have to support this kind of community development. Our first big step is going to be getting a comprehensive survey done of our existing housing stock and what our projected needs are. Once we know where we are, then we can start putting together a comprehensive strategy that will provide the housing resources we need at all levels—temporary shelter, transitional housing, affordable rental housing, affordable homes for entry-level buyers, and an attractive supply of middle-class, single-family homes. There are a lot of moving parts to this imitative, and it will be a LOT of work, but it has to be done. We absolutely cannot create a future where we can even survive, much less thrive, if we do not correct our housing challenges.