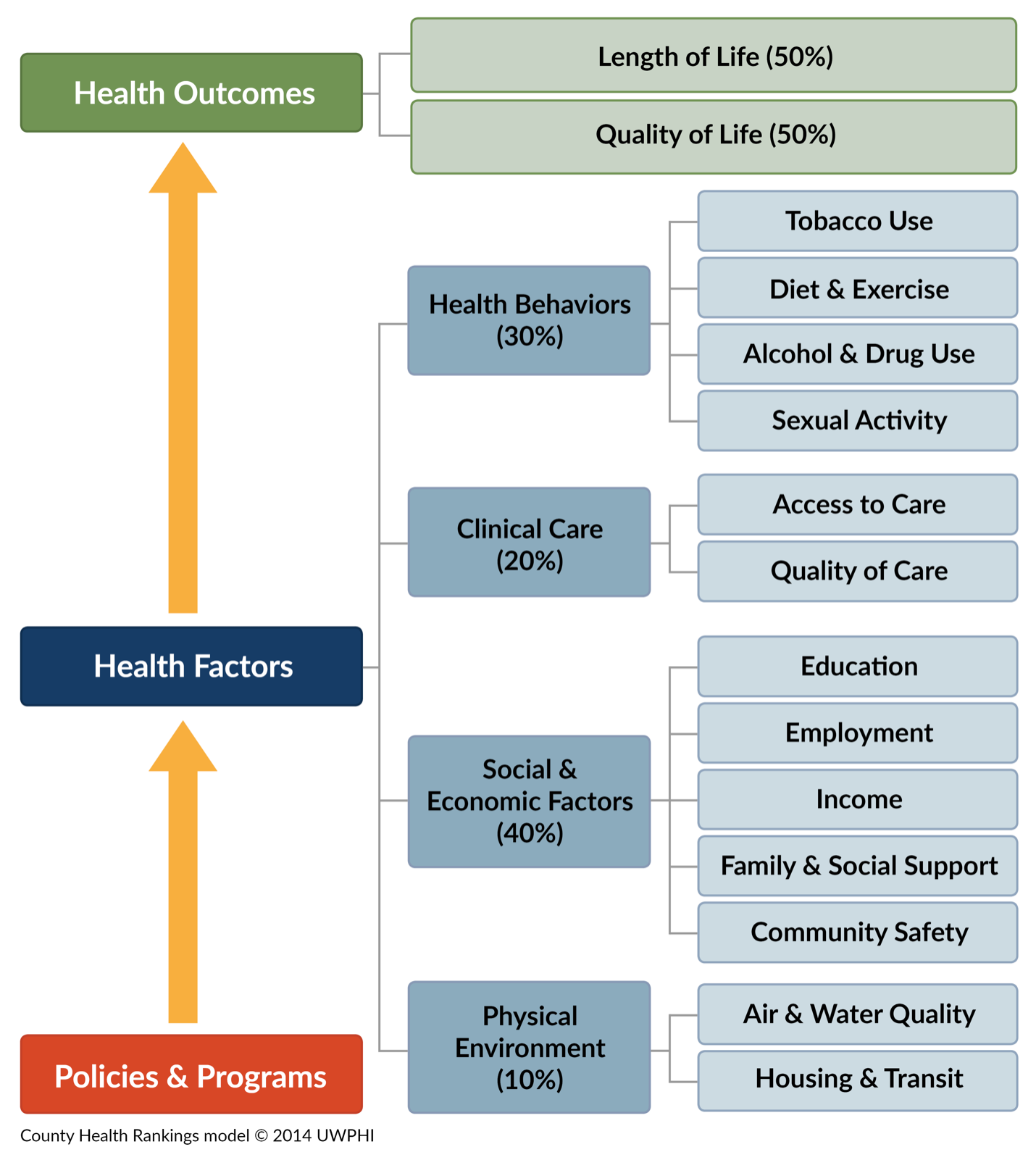

This is an article in a series about the issues that are dragging our rural communities down. The first four were an attempt to lay out the situation that we, here in rural western Kentucky, as well as in much of the rest of rural America, find ourselves in. The previous article, Ruralist # 5, was about housing, and like housing, substance use, and behavioral health (SU/BH) are fundamental issues that have very broad impact on the overall health and viability of our communities. Maslow is all about needs, not issues, so SU/BH don’t really have a spot on the hierarchy. Mental and physical health are sort of fundamental to being on the pyramid in the first place. As far as the Social Determinants health factors are concerned, substance use is part of “health behaviors” and behavioral health is under “clinical care”. It’s really important to understand, however, that neither of these subjects fits neatly into any category, instead, playing a role in multiple different areas. SU/BH issues often go together. For many people, they are “co-occurring” conditions. Substance use is very often a contributing factor to any number of other issues impacting a person’s life. Chronic pain, domestic violence, unremitting stress, grinding poverty and many other circumstances can underlie substance use. Similarly, substance use, and behavioral health issues can be root causes of homelessness, poor nutrition, crime, poverty, and more.

When we first established the ARCH Community Health Coalition, we knew that substance use, and behavioral health were going to be among the major challenges we would need to address. The opioid epidemic and the accompanying rise in overdoses have only exacerbated the situation. However, as we started working on issues like housing, we found out that SU/BH was very often part of whatever else we were looking at, so it has become one of our top priorities. SU/BH touches so many lives and so many other issues that we have to start addressing it directly or it is going to remain an anchor that is dragging our people and our communities down.

When I started researching into this, I knew little about SU/BH issues, except the fact that we have FAR too few resources available, particularly in rural places, to deal with the challenges. I’ve since spent quite a lot of time learning a little about the issues and about things that are working in other places to help make things better. I recently completed a year-long program called Reaching Rural, sponsored by the US Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Assistance, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and a couple other organizations that work in public health and criminal justice. It’s important to understand that the cooperation between public health and criminal justice is not actually an odd pairing. There is much more overlap between the two disciplines than one would think at first. The Reaching Rural program was designed to help rural communities learn how to build effective, collaborative approaches to SU/BH issues. Most of the participants were from interdisciplinary teams involving treatment providers, law enforcement, criminal justice, public health agencies and community-based organizations, like ARCH. Those who, like me, weren’t able to assemble a team participated as individuals. Through both the planned program learning opportunities and interactions with the other program fellows, I learned an incredible amount about many different projects that are working to help ease SU/BH impacts on people and rural communities just like ours. We have a lot to do, but the good news is that, for various reasons we’ll go into in a little more depth later, this is a uniquely good time to make some real progress in these areas.

So, here’s where we are now: Kentucky has some terrible statistics regarding SUD (substance use disorder), opioids and overdoses. Eastern Kentucky has been particularly hard-hit, but western Kentucky has also been hammered. Drug trafficking through this area is rampant because of our location along major east-west and north-south transportation routes. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation (a national health provider and research organization), Kentucky is in the top 10 states most heavily impacted by the opioid crisis. Our overdose mortality rate is almost 50% higher than the national average. We had the second-highest increase nationally in the OD rate since Covid and the rate more than doubled between 2011 and 2021. In 2021, 1897 people died from opioid related overdoses in Kentucky, with another approximately 500 OD deaths from all other substances. These stats just illuminate drug-related deaths, they say nothing about the suffering, economic impacts, crime and misery associated with SUD.

How did we get here? Interesting question without a good single answer. Part of the answer is that we didn’t just get here. We’ve had serious substance use problems in our area for a very long time. In fact, the TV news magazine, “60 Minutes”, did a segment on the heroin problem here, back in 1975, because Madisonville had been hard-hit by the growing drug problem and was representative of the issue that was sweeping through rural America, having already penetrated the cities and the suburbs. The “War on Drugs”, which was the federal government’s policy on addressing drug use, was officially launched in 1971. It didn’t work then and it’s never worked since. Much like Prohibition, which did nothing to curb alcohol consumption but, instead, firmly entrenched organized crime into American society, the War on Drugs, has succeeded only in making the US the number one country in the world for the per capita number of incarcerated people and making drug cartels into incredibly powerful, wealthy and violent plagues on the Earth.

Many of policies we’ve enacted over the years to address drug-related issues have been perfect examples of the Law of Unintended Consequences. For instance, our efforts back in the 80’s to destroy the source of the cocaine being shipped into the country succeeded only in creating the massive cartels that have since come to dominate much of the international drug trade. The appearance of crack and its horrific effect, particularly on American inner cities, came about because so much powder cocaine was coming into the country that the price dropped, so dealers started converting powder cocaine into crack because it was more potent, more profitable and could be sold in smaller amounts, making it more accessible to lower-income users than cocaine powder. The manufacturing of methamphetamine started out as a “cottage industry”, where relatively small amounts of meth were produced in many small “labs”. Cleaning up those local, small-time operations, while obviously a good and necessary thing, drove the development of industrial-scale facilities in other countries which has had the unfortunate effect of making meth both cheaper and more available.

Opioids have been used and abused for centuries, even playing a significant role is major global events. Opium smuggling, for instance, was a key part of the tea trade back in the 19th century. Great Britain and China actually fought wars over it. To a considerable extent, the founding of Hong Kong as a British colony came about as a result of the opium trade. Opium, primarily in a liquid form, called laudanum, was used medically as a painkiller in early medicine. Opiates are still very widely used as the most potent pain-killers available. While there have always been people addicted to opiates, the widespread recreational use of opiates, primarily heroin, didn’t begin in America until the late 60’s and 70’s. Our current opioid crisis is actually due to much more recent events.

We’ve had an SUD problem for at least fifty years. If you include alcohol use in that, we’ve had a problem since roughly when the first grape started to spoil. If you don’t have personal experience with SUD (or behavioral health), it’s a certainty that you know people who do, whether you know it or not. You went to school with them. You work with them. You go to church with them. They are right there, and they always have been. It not a “them” and “there” problem. It’s an “us” and “here” problem. It's a simple, unfortunate fact.

Our current opioid crisis stems from the development of new narcotic pain relievers in the mid-1990’s when Purdue Pharma developed Oxycontin, a semi-synthetic, slow-release narcotic pain reliever. The development of the drug wasn’t the problem. The marketing and promotion of the drug were. Oxycontin was aggressively marketed to physicians as a safe alternative to traditional narcotic pain relievers, with a much lower potential for addiction and abuse. Unfortunately, that was a lie. However, the marketing of Oxycontin and other Oxycodone-related drugs resulted in much wider prescribing by doctors, who believed it was safer than other alternatives. The prescribing of pain relievers increased about ten-fold in the five years between 1997 and 2003. Many patients became addicted, and as Oxycontin became more available, it became a drug of abuse on the streets as people learned to simply crush up Oxycontin tablets to get the full dose immediately. So began the current opioid crisis. That’s all bad enough, but things got even worse when awareness grew of the huge problem the over-prescribing of Oxycodone-related pain killers was causing. As the scope of the tragedy became known, physicians started to sharply curtail their prescribing and many states put in place mechanisms to monitor and control dispensing of potentially dangerous drugs, such as pain medications. Law enforcement started working to shut down “pill-mills”, which were just medical practices run by unscrupulous physicians who prescribed millions of pills over the years. The problem was that all these people using Oxycontin and other related prescription opioids, whether for legitimate medical purposes, or not, were already addicted. When the supply of “legitimate” prescription drugs dropped sharply, addicted people had to turn to street drugs, like heroin and, later, fentanyl, to stave off the agony of withdrawal.

That’s how we got where we are. Opioids (and other drugs) are brutal. They completely take control of people’s lives. People with addictions aren’t just criminals or weak-willed pleasure-seekers. The majority of opioid addicts probably got that way by just following doctor’s orders. Many of the rest fell into the thrall of addiction before they even realized what was happening to them. Although some of them made the unfortunate decision to start down the path, none of them chose to become addicted.

The good news is that we’re developing a much better understanding of both addiction and behavioral health issues and the role they play in other aspects of individual and community health. As understanding has grown, so have the resources we have available to address these challenges. We don’t have to figure it out for ourselves. Effective programs and approaches to deal with SUD/BH have already been developed in places just like ours. All we have to do is adopt those solutions for our own situation. What we need is a comprehensive approach to dealing with addictive substances and behavioral health issues, as well as the consequences those issues have on people, their families and the communities they live in. We propose the creation of a collaborative, region-wide, strategic approach to address these challenges.

One note: Substance use and behavioral health are not the same, but they often occur at the same time for people dealing with them. The approaches to both are also often similar, as is the intersection of both with law enforcement and criminal justice. What follows isn’t meant to cover all facets of behavioral health. There are obviously a lot of challenges we need to address before we are in a position to treat behavioral health as what it really is, which is just another aspect of health, full stop. In this article, we’ll just be discussing behavioral health in those ways that it tends to parallel substance use as a community health issue.

Item 1, Education and Prevention: Any comprehensive approach to SUD/BH starts with awareness. There is a stigma associated with both SUD and BH issues that has persisted for many, many years. Many people suffering from them feel a degree of shame, because so many of us look at them as failings or weaknesses. Most of us know that this isn’t true, and public awareness is growing that these are human health challenges that need to be met with compassion and understanding. Step one in our comprehensive approach then is education to increase awareness and remove stigma. Coupled with SUD education is also prevention. If ever there was an instance where an ounce of prevention truly is worth a pound of cure, SUD is it. By far, the most effective way to deal with SUD is to prevent people, particularly youth, from ever getting involved with potentially dangerous substances (including alcohol, tobacco, vaping and drugs) in the first place. There are lots of ways to do this, and many organizations and agencies are already doing it. One way we can make our education efforts more effective is to develop standardized, age- and culturally appropriate messaging and to adopt it throughout our region. By doing this, we can maximize the impact of our resources and make sure that the right messages are getting out to everyone. This is probably the easiest part of the plan to implement and can start to be rolled out fairly quickly after we establish our collaborative working group.

Item 2, Harm reduction: The term “harm reduction” is one that pushes some people’s buttons because they equate it with “enabling”. Some think that if you reduce the risk or the negative consequences of a behavior, then you are, after a fact, encouraging it. I get this perspective, and in some cases, I agree with it, just not in this case. Most of the people with SUD will fail to quit many times before they are able to overcome the addiction, once they begin treatment. Until they are able to get out from under, it is most definitely in both their interests and the interests of the rest of us to help mitigate the potential harm resulting from SUD. It’s not only the decent thing to do, but also the smart thing, because harm reduction measures cost much less than dealing with the consequences of doing nothing. Overdose is not the only negative health outcome of substance use, particularly with opioids and other new drugs appearing on the scene. One issue is that injecting drugs carries a whole host of other risks, including HIV/AIDS, hepatitis and infection. There is a new drug, xylazine, that is now becoming more common on the streets. It’s been used for years as a tranquilizer in veterinary practice, but it’s never been approved for use in humans. I used to use it myself when I was still doing research. People who use fentanyl and other drugs sometimes add xylazine for various reasons. Not only does this increase the risk of overdose, but the long-term use of xylazine also causes skin abscesses and the appearance of deep lesions in the tissues into which it is injected. These wounds don’t heal and often get infected, causing all sorts of medical consequences. Harm reduction means exactly that—reducing harm to people. If someone is still using drugs, keeping them from dying from an overdose is harm reduction. Providing clean needles so that they don’t spread blood-borne diseases by sharing and reusing needles is harm reduction. Providing wound treatment to avoid infection is harm reduction. On a larger scale, providing supportive housing where people suffering from SUD and BH issues can live in an environment that provides the supports they need while they are trying to get their lives in order is harm reduction. Again, none of this is enabling. If you want people with SUD and BH issues to get better, you remove as many barriers to healing as you can. This isn’t some crackpot, “woke”, progressive, liberal theory. It’s been done, and it works. It’s both right and smart. Again, there are lots of organizations providing harm reduction supports in our area. We can just maximize the impact and minimize the cost if we develop a collaborative, regional approach so that what is needed gets to where it’s needed. Larger-scale things, such as the development of supportive housing, is something that definitely requires a regional strategy, as it won’t be feasible to put a supportive housing facility in every community.

Item 3, Treatment: SUD and BH issues respond to treatment, just like any other health conditions. The thing about treatment, though, is there generally needs to be someone to provide it, and that’s where we are lacking. Most everyone has heard about the lack of sufficient mental health professionals. This is an issue most everywhere, but as is usually the case, the lack is more pronounced in rural places. There simply aren’t enough psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists, counselors and other providers for either BH or SUD to go around and most of them chose to do what they do in more urban settings. This lack of providers, in all areas of medical care, is one of the more serious challenges facing rural America. Our area is underserved in all aspects of SUD/BH. We have some outpatient resources locally and a few inpatient resources for both BH and SUD, but not nearly enough. It is a constant struggle to find transportation for people needing long-term, inpatient SUD treatment because there isn’t much on this end of the state. One thing we need to work on with our collaborative is to develop a transportation network to help people get to the treatment resources they need (among other things. Transportation is a HUGE need in our region). Another is to start developing more regional treatment options, to include long-term treatment. Beyond that, we need to come up with a collaborative approach to transitional living facilities for people in recovery, once they complete their formal treatment program. We have nowhere near the resources for this that is needed, and it’s key. Having someone leave treatment and return directly into the environment that contributed to their SUD or BH issues in the first place is madness. People need a safe place to go to get their lives back on track. Sober-living and other transitional housing is just a requirement. We have some, here and there, but this is another area where collaboration will be extremely effective.

Item 4, Avoiding unnecessary involvement of law enforcement and criminal justice in SUD/BH-related situations: Right now, most of our response to situations where SUD or BH is a factor involves the police, whether or not there is any criminal activity. This is both not helpful for the people involved and a waste of public safety resources. Often, when police get involved in a situation that needs SUD or BH help, they end up spending hours hanging around the ED when they should be out in the community. There are a number of alternatives to this that have been shown to work in other places. These alternatives generally involve what are called “rapid response teams”. These teams are comprised of people skilled in handling SUD/BH situations. 911 dispatchers can use the teams in a couple of different ways, depending on the situation. Where there is clearly no safety or crime issue, the rapid response teams can be dispatched to the scene by themselves. In other cases, the teams can accompany police and attend to the situation as appropriate, with or without further police involvement. Keeping our jails and courts from being jammed up with people who aren’t criminals is a win-win. This initial response is only part of the process, however. The other is having a facility where these people can be taken where their conditions can be stabilized and assessed to determine what the appropriate next steps are, in terms of treatment. These types of facilities are generally referred to as something like a “Crisis Center” or “23-hour Crisis Center”. The 23-hour part, as I understand it, is important for a couple of reasons. First, it generally allows enough time for a person with SUD to be regulated. It also allows time to assess patients with mental health issues or suicidal ideas to have a start on their treatment. It also allows the facility to be flexible because if a patient is held for more than 24 hours, the regulatory situation becomes more complicated. Some people who go to a crisis center may be discharged, or they may be recommended for a level of continuing treatment. In any event, the crisis center is a much more appropriate setting for these initial treatments and assessments than an ED, and the result is people end up getting the help they need in an efficient process. We do not have a crisis center in our proposed region, and the immediate planning for one (or more, if necessary, based on projected volume and geography) should be a goal of our collaborative.

Item 5, Incarceration, Adjudication and Re-entry: Obviously, some people with SUD/BH issues will have committed crimes. Some of those people will be sentenced to jail time and some won’t. How we deal with these folks, in court, in jail, and upon release from jail has a great deal to do with the health and long-term prospects of the people involved. Again, there are excellent models for programs that have successfully addressed these sorts of issues in other rural places. If, during an incident where the police and a rapid-response team have evaluated a situation and it appears that a crime has been committed, an arrest will be made and the individual, after they are stabilized, will be sent to jail to await arraignment. This is an opportunity to take proactive steps. One approach is to have SUD/BH counselors present in the jail to evaluate all people who are admitted, prior to arraignment. The counselors then write up a summary of their evaluations which is provided to the judge prior to arraignment, which can be done either over a video link or in the courtroom. These summaries give the judge insight into how the individual might best be dealt with, whether that is through the regular criminal court process, drug court, therapy, or other options. Having the information to be able to make these determinations saves the courts time and money and gives the offenders the best options to correct their situations. Individuals sent to diversion programs need broad support if the diversion programs are to be successful. Hopkins County is part of a pilot program to provide these supports, which include active case management, social supports, employment training, peer support, life skills coaching, parenting classes and more.

Those individuals with SUD/BH issues who do end up in jail still require support and treatment for their conditions during incarceration. Having those appropriate options in place in the jails produces better outcomes. After incarceration, it has also been shown that supportive services provided to people as they re-enter society lower the risk of recidivism and re-offending. If a person leaves incarceration and is just released back into the same situation and same environment they were in before without support, it’s a good bet that they will be back in jail shortly. Supportive programs during incarceration and re-entry have been shown to help keep people out of jail and in the productive workforce, which should be the goal.

“The way we’ve always done it”, in regard to SUD/BH, particularly when law enforcement and the criminal justice system gets involved, has never produced the sorts of outcomes we seek. Trying to arrest our way out of the problem and filling jails up with people who have SUD/BH issues has never and will never work. There are better ways that both protect our communities from criminal activity and also help the people who can be helped get back on the path to being productive citizens.

Item 6, Supportive Housing: As I’ve mentioned before in this series of articles, housing is one of the fundamental issues at the very base of the hierarchy of needs that impacts pretty much everything else, and for people with SUD/BH issues, it’s certainly no different. If anything, it’s even more important for these folks than for many others. If you’d like to see an in-depth look at our housing situation, please see my previous article in this series, Ruralist #5.

Homelessness very often is tied to SUD and/or BH issues. Many people wind up homeless because of the impact of SUD or BH issues, or else they develop SUD or BH issues because they are homeless. Whether it was the chicken or the egg, the presence of SUD/BH issues often will prevent homeless people from being able to get back on the path to stable housing. This is one of the situations that supportive housing was designed to address. Putting people with these sorts of complex issues into a safe, stable housing environment is the first step on the path back to a healthy, productive life. Note that I said “first step”. That is the key to supportive housing. It used to be that getting sober or getting BH issues stabilized was a precondition for people to get into housing. The thinking was that being able to get housed was a “carrot” that would incentivize people to get treatment. While this is not an unreasonable point of view, it turns out the “stick” of addiction or mental health issues is a far more powerful influence than the ”carrot” for most people, so they never find themselves able to access a safe, supportive housing environment that would enable them to take the steps they need to take to get into recovery or treatment. Hence, supportive housing.

In a supportive housing facility, the first step is to get people into a safe place. Sobriety or treatment is a goal, not a condition. Once a person is housed, the supportive housing facility provides on-site counseling, care and treatment services, as well as built-in network of peers who have gone or who are going through the same things, when a person is ready and able to take those next steps. Supportive housing works. It gets people into treatment and recovery programs, and more importantly, the people who go through supportive housing and then move out into “regular” housing, tend to stay in recovery and remain stably housed at a higher rate than people who don’t have access to supportive housing.

Another aspect of housing that is not like the supportive housing described above is transitional housing for people coming out of treatment programs. We are all aware that people with SUD often relapse after they leave treatment. Sometimes people have to try many times before the recovery “sticks”. Part of that is just due to the insidious, all-consuming nature of addiction. Another part is much simpler. As a general rule, once a person leaves treatment, or while they are in treatment, if they are going through an outpatient program, they are right back in the environment that contributed to their addiction in the first place. In that situation, it’s almost a certainty that they will find themselves vulnerable to the same pressures that led to their problems. One solution is called something like transitional housing or sober-living homes. There are a variety of approaches, but they all provide a safe, supportive, drug-free environment where people in recovery can concentrate on getting their lives back on track. Most places provide counseling, employment supports, life-coaching and other services that help people build a strong base from which they can get back to healthy and productive life.

The ideas presented in this article aren’t a bunch of liberal nonsense, as some people may choose to think. These are ideas that were developed and implemented by people in law enforcement and criminal justice, along with healthcare and social service providers to change processes that were not working in their communities. I have personally visited a rural community that is doing these things, and more. The person who helped devise the program and who directs it is the ex-Chief of Police for one of their larger communities. He’s hardly and “rainbows-and-unicorns” kind of guy. The bottom line is that it is working for them, and it will work for us here, too. We just have to do it.

To jump-start this process, we’ve established a regional coalition of organizations and agencies that play a role in SUD/BH. Right now, it’s called the West Kentucky Substance Use Collaborative, which isn’t a very good name, and the acronym (WKSUC) is awful. Hopefully, someone will come up with a better name soon. In any event, the purpose of WKSUC is to get the right people around the table. Developing the strategies and plans for these ideas and then implementing them is going to be a major undertaking. We’ve taken the first step by establishing WKSUC, but we have only begun to reach all the people who need to be part of the effort. Our next step is to find the financial resources to support the planning and early implementation of the project. Unfortunately, we do not have the luxury of time. There is a very great deal to do and every day we don’t get it done, people are suffering, and it is costing us and holding us back.