I hate jargon. “Jargon”, according to Merriam-Webster, is “the technical terminology or characteristic idiom of a special activity or group”. According to regular people, jargon is all the unfathomable words and phrases used by people who specialize in certain things that none of the rest of us can understand. The first time is saw the phrase “socioeconomic determinants of health” (more commonly now “social determinants of health, SDoH), my immediate thought was “here we go”. However, as is the case for most jargon, there really isn’t a better way to say it. It means exactly what it says—the non-medical factors that impact health.

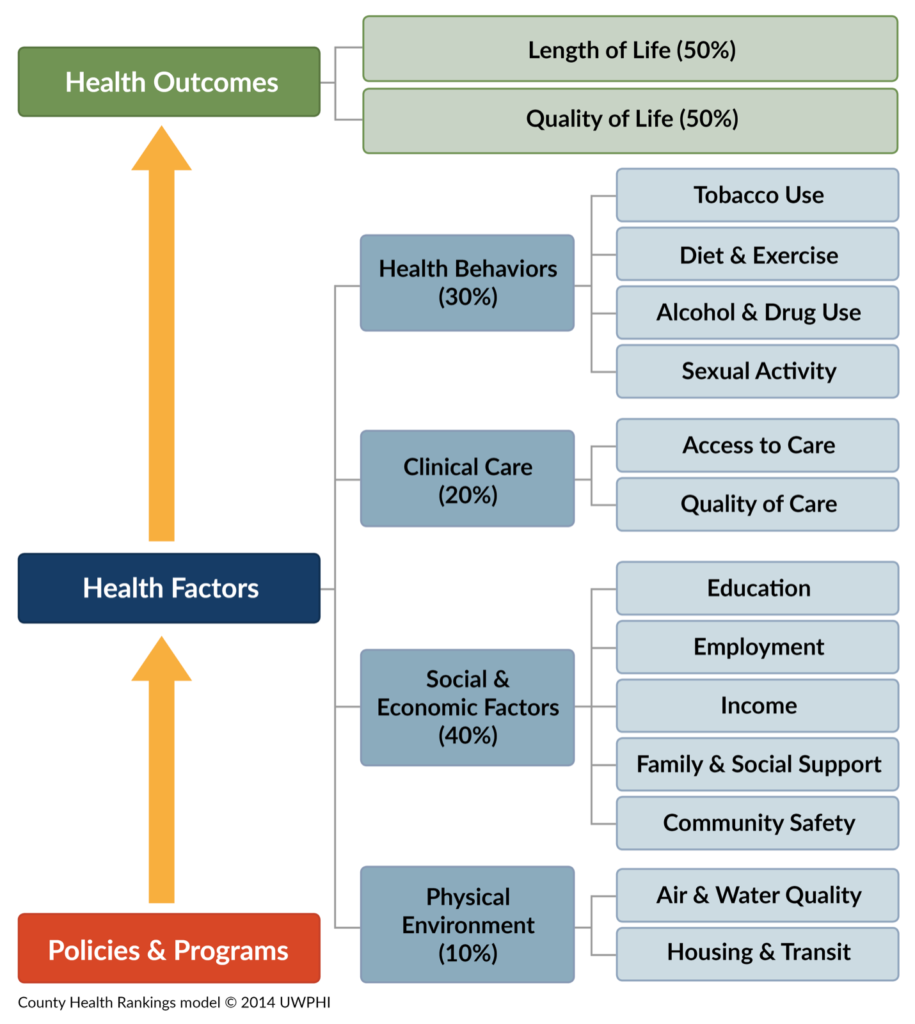

The image below illustrates the concept. It was originally created by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Public Health Institute. On the left side are three related boxes. At the bottom is “Policies and Programs”, which are all the things that influence what we do. That determines “Health Factors”, which are all the things connected to it, to the right, like “clinical care” and “health behaviors”. Those Health Factors determine Health Outcomes, which is divided into “Length of Life” and “Quality of Life”. The best part of this graphic is the Health Factors, and we’ll go into most of them in some detail in the rest of this series of articles. We’ve already touched on some of them in the previous ones.

For now, the important thing I want you to grasp is in the four main health factor boxes. Under “Clinical Care” is 20%. This means (and there are lots of other studies from other organizations and government agencies that agree) that only about 20% of what determines if you are healthy or sick has anything to do with doctors, hospitals, medicines and all those other things we typically think of when we think of health. The other 80% of what determines our state of health is mostly how and where we live, i.e. the Physical Environment (10%) in which we live, play and work; Social and Economic Factors (40%), which largely impact the resources available to us throughout life; and Health Behaviors (30%), which are mostly the choices we make about what we do with our bodies and what we put into them. The concept of the Social Determinants of Health is not some off-the-wall theory someone cooked up to support a crackpot idea. This is something that has come about through a lot of research and experience over many years, and it reflects of the reality of our individual and community health, or lack thereof.

Here’s an example that I use to illustrate the impact of SDoH: There’s a 9 year-old girl who ends up in the Emergency Department with an acute asthma attack. Fortunately, it’s fairly easy to treat and she gets her steroid injection and goes home. Unfortunately, she’s going to be back in a month or so with another attack, and everyone knows it, because she’s been a regular patient in the ED for over a year. She’s going to be back, because her house is full of black mold and that’s what sets off her asthma. Why is the house full of black mold? The mold is there because the pipes under the kitchen sink leak. If you want to prevent this girl from having these asthma attacks, what she really needs is a plumber, not and doctor, but we really don’t have a system for getting pipes fixed. So we go on, spending thousands of dollars every month or so to deal with these attacks (not to mention the effects the attacks have on the poor girl) in the ED when the problem could be eliminated by spending a few hundred dollars on a plumber to fix the pipes. Her problem isn’t that she has asthma. Her problem is where she lives. Let’s follow this story a little further. Why are the pipes leaking? Because her mom can’t afford a plumber. Why can’t she afford a plumber? Because she doesn’t have a decent job. Why doesn’t she have a decent job? Because she has no job skills. Why doesn’t she have any job skills? She has no job skills because she can’t get through a job training program. Why can’t she get through a job training program? Because she can’t get through the coursework. Why can’t she get through the coursework? She can’t get through the classes because she has a substance use disorder. Why does she have a substance use disorder? It’s not because she “made bad choices” or “because she’s weak” or “because she’s a criminal”. She has a substance use issue because she had a car wreck two years ago and she get addicted to prescription pain medication that was prescribed for her. So, if you want to really deal with that little girl’s asthma attacks and stop spending thousands of dollars a year on unnecessary visits to the ED, what we really need to do is to help her mom get through a treatment program so she can get some training, get a decent job, make some money, pay a plumber, and get rid of the mold. And until we do those things—all of those things—we’re just going to be dealing with the consequences of not doing it, over and over again. One of these approaches is WAY better than the other, and it’s cheaper, too. That’s what the “Social Determinants of Health” means.

So, if clinical care only accounts for 20% of what impacts our health, why do we spend so much money on it and put so much emphasis on it? Well, as it turns out, that’s an excellent question that people have started paying a lot more attention to over the past several years. It’s also a great example of how even something as enormous as the American healthcare industry can change when new information warrants it. If healthcare can adopt new ideas, so can you and I.

The “way we’ve always done it”, in relation to healthcare, is often called something like “episodes of care”. It’s when you get sick and go to the doctor to get treated or, if you’re sick enough, get sent to the hospital. An episode of care starts when you realize you are sick and ends when you either get better or die. Someone will then pay for this “episode”. The newer way of looking at healthcare is called “patient-centered” care or “value-based care”, depending on who is talking. People who provide care call it patient-centered. People who pay for it (insurance companies, Medicare, etc.) call it value-based. Whatever. What it means is that instead of a patient showing up in a doctor’s office to get treated when something bad happens, there is an effort to address all those social determinants and engage in preventative care to help keep people from getting sick in the first place. As it turns out, this is not only obviously a good idea for the people, leading to healthier, longer lives, it’s also usually WAY cheaper than the episodes of care model.

Again, an important point about this is that addressing the SDoH doesn’t end with healthier people and communities, because health is just the basic part of living. Doing the things we need to do in order to be healthier is a necessary part of trying to build more sustainable, prosperous communities. Going forward in this series of articles, we’ll look at these issues and some of the things that we are doing and that we should be doing to address them. Keep in mind the SDoH diagram and the Maslow pyramid as we go. Many of these issues are interconnected, so it’s difficult to talk about one thing (employment, for instance) without also talking about other issues (like transportation) at the same time, but that’s actually a good thing. It helps to reinforce the connectedness of the issues. If you recall when I was explaining why we started the ARCH Coalition, I mentioned how we thought it was important to take a very broad-based approach to the issues and to act on a regional basis. This is why. We can’t pick one thing to work on. First off, we don’t have time. These are complex issues that are not going to be fixed in a year, or five, or probably even ten. Some of this stuff is the work of generations. Most of our rural communities are in crisis now. They won’t survive as viable communities for long enough for us to work on one ten- or twenty-year project at a time. It’s great to be able to focus on one thing, but we don’t have that kind of time. We have to move forward on multiple fronts and we need to start now. Besides the time factor, is also this interconnection between issues. There is simply no way to separate them if we are going to develop effective solutions. It’s a huge task, but the decisions about what to do and when to do them are made a lot simpler by the fact that these are things we HAVE to do and we have to do them now.