That title is not a value judgement on anyone’s priorities. It’s just a phrase that grew out of a Presidential campaign back in the 1992 and it is a marvel of snarky simplicity. I’ve always sort of thought about it as a reminder of how, even though there are any number of seemingly unrelated, humongous issues out there, they often converge in one place. It helps to clarify the thinking.

If we start with the ideas that our community, like many others, is a “company town” that has lost its primary economic engine and that a declining population with the related effect on the workforce is absolutely unsustainable, both of which are pretty much unarguable, then we next need to figure out what to do about it. What are our assets and liabilities? What can we change and what are we stuck with?

Here’s a point that I need to make very clear, and it may require some different thinking for some of us, but that’s okay. We are rural. The defining characteristic of rural is a small population spread over a large area. This has two very important consequences. First, people are our primary limiting factor in terms of our economic potential. When we have more people participating in the workforce, we are all better off for lots of reasons. The second major consequence of rural is that low-population density also makes it more difficult and expensive to acquire resources than in more urban, higher-population areas because of economies of scale. We see this all the time in rural places. It’s much easier, for instance, to find certain services, like a therapist, in a large city than it is in a small town. This same factor impacts other resources, like social services, as well. There is nothing we can do about our population density, and most of us wouldn’t if we could. A lot of us live in rural places specifically because we like the space. What we can influence, however, is the people. There is another aspect of productivity that we will address in later articles. It is that the productivity of any community depends not only on how many people are working, but also the added value that their work produces. Lots of people doing low-value work may be less productive for a community, overall, than a few people doing high-value work. The ideal situation then, is having as many people as possible engaged in the highest-value work of which they are capable.

I’m guessing that most of us can agree with all that. They are relatively straightforward concepts. What they mean for us is where we’re really going to have to put in the effort. If, as we’ve established, the number of people available to participate in the workforce is our main limiting factor for increasing productivity and, thus, prosperity, we need to increase that number (let’s leave the value-added part for later). Again, this is something we can all probably agree on. There are several ways we could achieve that goal. One is to retain more of the people, primarily the younger folks, who are leaving our communities. This is a difficult path, because there are a lot of reasons people leave, many of which are out of our control. The few things that we can work on are mostly complex issues with few short-term solutions. Most young people leave because, well, they are young. They want to get out and experience the “bright lights” that more urban places offer. They also want to pursue educational and economic opportunities that are not readily available in our small towns. Hopefully, some of them will come back after they complete their educations or when they want to settle down and raise a family. Enticing them to stay is a pretty tall order, but there are some long-term things we can do to help, mostly involving better job opportunities in the types of work that they are attracted to. Trying to attract them to return to raise their families actually plays to our rural strengths, in some ways. Rural places tend to have lower costs-of-living, especially in regard to housing costs, and that’s attractive to young families looking to buy homes. It’s also a good selling point for retirees who will find that their retirement incomes go further in rural places than in larger towns. We will talk about things like aging and retirement in another article. Those young families will be looking for quality housing, good schools, good community dynamics and other quality-of-life issues.

So, keeping our own people from leaving or getting them to come back is one way to slow our population decline and increase workforce. Attracting younger retirees looking for second careers is another way. Bringing in people who have no previous ties to the area is a third. This one is very dependent on economic opportunity. In most cases, the only reason people from the outside will move into a new community is to improve their economic situation (unless they are in witness protection, or something like that). All three of those would require long-term strategies to change the local conditions, which is fine, because changing the local conditions is what we’re going to have to do, anyway, if our rural communities are to survive and thrive. There is, however, one approach to expanding our productivity and our workforce that will generate better returns, beginning sooner than those. That idea is to mobilize the parts of our exisiting population that are not currently in the workforce to join or re-join it. This is where things get interesting.

Kentucky has a relatively low workforce participation rate. It is currently 56.9 percent, compared to the national rate of 62.5%. It is lower still in much of our region, often in the low 50s. This is a measure of what part of the local working-age population that is working or trying to find a job. There are many contributing factors to why our workforce participation is low, and we will go into each in detail in later articles. We will briefly touch on some of those factors now. One big reason is that we are a very unhealthy population. Our rates for obesity, diabetes, heart disease, pulmonary disease, and cancer, among others is much higher than national averages. The health of our population plays a major role in the size and productivity of our workforce, and that, in turn, plays a part in employers’ evaluation of our area when thinking about new facilities. Improving individual and community health will lower sickness and disability, adding to our workforce and our economic potential.

Another factor contributing to our low workforce participation rate is childcare. Like many places, we have a serious shortage of available, affordable, quality childcare options. The lack of childcare has many implications for workforce, for employers and for our kids, too. There is huge potential upside for improving the childcare environment here and throughout rural America.

Substance use and behavioral health issues have major impact on our communities with all sorts of impacts on productivity, health and quality of life. We haven’t ever really dealt well with these challenges, and they have far-reaching effects from disability to engagement with criminal justice to healthcare costs, preventable deaths and more. This is one thing that we absolutely must start dealing with more effectively.

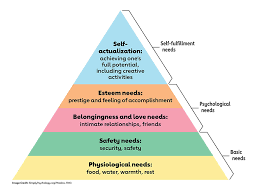

Housing is a big problem here, as it is throughout the country, rural and urban alike. Part of the problem is availability. There just isn’t nearly enough decent housing available. Another issue is related to that, which is affordability. Housing, along with food and clothing are the most basic of human needs. It’s almost impossible to do anything else until those needs are met. The image below is called “Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs”. It’s a graphical representation of human needs that illustrates how we have to fulfill the basic requirements before we can move on toward achieving other, more advanced stages. The image is a pyramid for a reason. One MUST start at the base and build upward. Much of what we’ll be going over in these articles is about just this. If we want people who are being held back from being the people they could be, we have to help remove the barriers that are preventing them from acquiring these basic needs. There are no shortcuts. If you want somebody to dig a hole in return for a reward, you better be prepared to make sure he has a shovel.

Infrastructure is something we’ve been hearing a lot about, particularly in the last year or two. Usually, when we hear the word, “infrastructure”, we think of things like roads and bridges. That’s part of it, but it also includes things like public transportation, broadband, recreational facilities, medical facilities, childcare centers and other public resources. We’re entering a unique time where it’s going to be possible to do a lot of things that we’ve not done before.

There are other factors we’re going to need to address if we are going to have the kind of future we want in rural Kentucky, or rural anywhere, for that matter. A lot of these issues are what we generally tend to think of as social issues, and many of us start to get our hackles up as soon as anything like that comes up. I hope I have begun to make a case that these issues aren’t just liberal “kittens and unicorns” boondoggles to help undeserving people avoid the consequences of their actions. In most cases, they are anchor chains holding people back who want to live better lives. In the articles to follow, I’ll try to make the case even more clearly. These are not “liberal” issues or “conservative” issues. These are economic issues that we are going to have to address or our failure to do so is going to drag down everything we are trying to preserve and build upon for the future.

One final remark about the economics of this. We have spent a LOT of money, particularly over the past fifty years, trying to improve some of these issues, and the issues remain. Part of that is the perspective caused by the filter of time. Yes, the issues still remain, but they’ve improved, and some have improved a lot. For instance, it’s been a long time since we have had a river so polluted that it caught on fire. That doesn’t mean we can stop working on water quality, but it does mean we’re getting somewhere. We need to realize, though, that most of the resources and effort we’ve spent on these issues have been spent, not on the root causes of the problems, but on the downstream consequences of those problems. The consequences tend to be more visible, more immediate and more tractable than the deeper issues, so that’s where most of our effort has gone. When a child is hungry, the first thing to do is give him something to eat. That doesn’t solve the problem of WHY he is hungry, but that “why” is probably a complex situation with no easy fixes. Dealing with those consequences, for a long time, was just about all we could do, but the problem with that is you have to just keep doing it, over and over, because the situation underlying it doesn’t change. We, as a society, are now entering a time where we have the ability to finally discover and work on those root causes. We know more than we used to. We understand more than we used to. We finally have the economic strength and technological capacity to do the things we’ve never been able to do before. The wonderful thing about it is that, once we lift a person out of whatever was preventing them from finding their potential as a productive member of our communities, we not only have someone who can contribute, we no longer have to spend resources dealing with those consequences.