I don’t know about y’all, but when I hear or see things related to the coronavirus, I kind of feel like I walked into a movie in the middle. I thought I might try to fill in some of the missing holes in the plot. Before I do, however, I want to make it clear that I am not a physician and nothing that follows should be taken as medical advice. If you have medical questions, please refer them to a physician or other qualified health care professional. I am also not an Epidemiologist, who are scientists who specifically study the transmission of infectious diseases. Nor am I a Virologist (studies viruses) or any other type of Microbiologist (studies microorganisms). I am a Physiologist. That means I have a better-than-average understanding of the structure and function of humans and of some of the things that can go wrong. Everything that follows is true, as far as I know, but it is possible that I might get something wrong. If I do and you catch it, please let us know so we can correct it.

Let’s start with some basics. Viruses are sort of unique in biology, in that they are not actually alive. They generally fall under the field of Microbiology, which is the study of organisms that are usually too small to see with the naked eye, like bacteria, protozoa, algae, fungi and molds. I say “generally too small”, because it’s sort of interesting that although things like viruses and bacteria are some of the smallest of all organisms (although, again, viruses aren’t, technically, organisms, because they aren’t alive) some of the largest of all living things are also fungi. Depending on how you measure things, the largest living thing on Earth may be a single fungus that covers almost 4 square miles in a forest in Oregon. Mostly, it’s underground, but every now and again, it sends up reproductive structures that we call honey mushrooms. But, back to viruses.

Viruses are very small. Most of them are smaller than bacteria. They are also very simple. Most of them consist of a single strand of genetic material, which can be either DNA or RNA (humans and most other organisms use only DNA to store their genes). Most viruses only have a few dozen genes. Humans have over 30,000 genes. “Genes”, by the way, are strands of DNA (or RNA in some viruses) that contain the instructions for how to make proteins. Proteins are complex molecules that make up much of the structure of cells and control how cells function. In the virus, this strand of DNA or RNA is surrounded by a shell of protein. There may or may not be a layer of fat, like a bubble, on top of the shell, surrounding the whole virus. If there is such a coat, it is called an “enveloped” virus. If there is not, it’s called a “naked” virus. Whether or not it has a coat has to do with how the virus reproduces. Viral reproduction is where we start to have problems.

Viruses are not evil. They have no intent or agency. They don’t mean to make people (or anything else, because some viruses infect plants or even bacteria) sick. Viruses do only one thing, which is reproduce. How and where they do it is how some viruses cause disease. Most cells reproduce by splitting in two, so one cell becomes two cells. All the cells in our bodies work that way, as do most other cells, including bacteria. Viruses can’t reproduce that way, though, because they are too simple. They aren’t cells and they don’t have the cellular machinery that allows them to divide and reproduce. To reproduce, viruses have to use the cellular machinery of some cell. To do this, the virus has to infect the cell.

“Infection” is actually a pretty broad term for when a microorganism (bacterium, virus, fungus, protozoan or parasite, like a tape worm) enters into another organism. We are, technically, “infected” with hundreds of different microorganisms under normal circumstances. Our intestines, for instance, are home to billions of bacteria. Our skins harbor all sorts of bacteria. Most microorganisms are not dangerous. Many, like most of the bacteria normally found in our guts, are actually beneficial to us. The bacteria in our guts help us to process water and some vitamins. One of the things that causes diarrhea is when the normal balance of bacteria in our guts gets out of whack. However, usually, when we think of infection, we think about some germ that is making us sick.

Pathogenic (meaning “disease-causing”) bacteria and viruses make us sick in different ways. Usually, when we have a bacterial infection, we get sick for two reasons. One is that when the bacteria reproduce very rapidly, they use up many of the resources that our bodies normally use for our regular function. When the bacteria use the resources, they aren’t available to our own cells and the cells don’t work right. That makes us feel sick in various ways, depending on where the infection is and what is causing it. The other thing that makes us sick from a bacterial infection is that the bacteria produce by-products by their own activity. These waste products are sometimes toxic to our cells. Sometimes they are extremely toxic. A product produced by the bacterium that causes botulism, for instance, is one of the most toxic poisons known. Viruses make us sick by first hijacking our cells and then, usually, killing the cells. As I said, viruses cannot reproduce on their own, so they have to use other cells to do it. Viruses infect specific cell types, based on which proteins the virus has in its outer shell. Our cells have certain proteins in their membranes that match the proteins on the virus. Different cell types match different viruses. This is why some virus cause respiratory diseases and some viruses cause intestinal diseases, for instance. When a virus finds the right type of cell, it infects the cell by either directly entering the cell or by attaching to the cell and injecting its DNA (or RNA) into the cell. Once the viral genetic material is in the cell, the cell takes the viral material and splices it into the cell’s own DNA. It then starts to make viral proteins. The viral proteins then assemble into new viruses. The cell continues to make new viruses, instead of doing whatever the cell is supposed to do. The new viruses are then either exported from the cell or accumulate inside the cell until the cell fills up with viruses and bursts. Once the viruses get out of the host cell, they are then free to go and infect other nearby cells, starting the whole process over again. So, one virus infects a cell, becoming many new viruses. Each new virus can then go infect other cells. You can see how quickly the number of infected cells can grow. So viruses make us sick by causing our cells to stop doing their normal function and then, often, by destroying the cells themselves, which in turn leads to inflammation and a cascade of other processes that add to the symptoms.

Because viruses don’t have any function other than reproduction, the don’t have a metabolism, like actual cells, including bacteria, do. By metabolism, I mean that the cells use energy and raw materials to live and grow and do things. Because viruses are so simple and don’t have any of the complicated biochemical pathways of metabolism, they usually don’t respond to drugs like antibiotics. Viruses don’t have anything for the antibiotic to attack. There are a few antiviral drugs for specific viruses, like HIV and the virus that causes hepatitis, but for the most part, viruses don’t respond to treatment with drugs. If a patient is getting medical care for a viral disease, usually what is being done is managing the symptoms, not actually treating the infection. Once you have a viral infection, the only way to get rid of it is for your own immune system to kill it. This is what happens when you get a cold. The virus infects the cells in the membranes of your respiratory system and for a while, the viruses reproduce freely and the damage they do to your cells cause the symptoms of a cold. Eventually, however, your immune system will overpower the virus, destroy them, and you get better. Sometimes, however, a virus reproduces so quickly or infects very sensitive parts of the body, causing so much damage that you die before your immune system has a chance to catch up. This is why infections that are normally no big deal for a healthy person can be deadly for the old, the very young or for those with immune systems that are compromised. Their immune systems aren’t working well and they may get sick enough to die before their immune response can take hold.

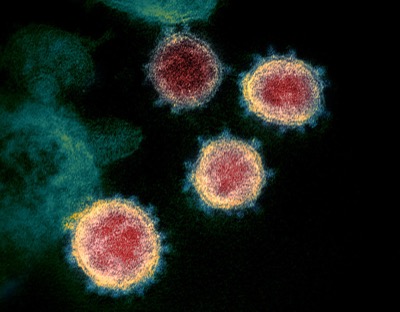

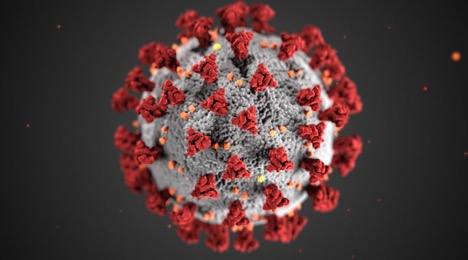

Coronaviruses are a very large family of viruses that are called coronaviruses because of the similar structure they share. They all have a circle of proteins around their shell that looks sort of like a crown. Most coronaviruses are not particularly dangerous. They tend to target cells of the respiratory system, but most of them just cause relatively mild symptoms, like a common cold. There are, for instance, many different coronaviruses that cause what we refer to as “a cold”. The current virus is being called a “novel coronavirus” because it is one that hasn’t been seen in humans before. Its official name is “Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2” or “SARS-CoV 2”. The disease it is causing is called, somewhat unimaginatively, “Coronavirus disease 2019”, or “COVID-19”. It is similar to the viruses that caused the SARS epidemic in 2002 and the MERS (Middle East Respiratory Syndrome) epidemic in 2012. Both the SARS 2002 disease and the MERS disease were more deadly than COVID-19 appears to be. SARS 2002 killed about 10% of the people who were infected. MERS killed over a third. COVID-19 appears, so far, to have about a 3% mortality rate. The difference, and what is causing so much concern, is that SARS-CoV 2 has spread much more quickly and much more broadly than either of those other two. Much is still not well-known about the virus and how it spreads, but it definitely is spread in droplets (from sneezing, coughing or even breathing hard) and appears to be at least somewhat persistent on surfaces, meaning that, for at least a little while, you can pick it up from a surface, like a tabletop or doorknob, where droplets were deposited. This is part of what is called “community spread”, if you’ve heard that term. It is much more difficult to control a microbe that can be transmitted indirectly, through community spread, than it is to control one that requires direct contact with or proximity to someone who is carrying the microbe. Another problem with the new virus is that so many people who become infected don’t develop symptoms. They don’t feel sick, so they go on about their business, spreading the virus to others. It also appears that the virus tends to infect most people over the age of 18 or so. Most of the deaths that have occurred have been in the elderly or in people with immune system issues.

What can you do? Well, as always, step one is to not panic. This is certainly a serious situation, but there’s no need to go out and buy all the hand sanitizer you can lay your hands on. Leave some for everyone else. There is plenty to go around. Hoarding is selfish, stupid and pointless. As of March 12, there are no instances of SARS-CoV 2 infection in Hopkins County or anywhere else in western Ky. There are 8 cases, statewide, located in Louisville, Lexington and northern Kentucky. This is not to say we don’t have anything to worry about. It is very likely only a matter of time before the virus is found locally. Our county leaders in healthcare, government, education and law enforcement are working closely with each other and with state and federal authorities. They are taking all appropriate and prudent steps to prepare for and manage the situation as it develops. In the meantime:

- Wash your hands. Do it right, with soap and water. To learn how to do it right, the CDC has a video. In short, soap up your hands, rub them vigorously together, getting front and back, in between fingers and around and under your nails. Rub for at least 20 seconds (“Happy Birthday”, twice or “The Alphabet Song” once). Rinse. Dry. If you are in a public restroom, leave the water running until you dry your hands. Then take the paper towel and turn the water off. Open the door with the towel and then throw it away.

- Don’t touch anything in public places that you don’t have to. For instance, push open doors with your elbow.

- Be mindful of touching your face, rubbing your nose or rubbing your eyes. Your mouth, nose and eyes are the routes through which the virus can enter your body. Your skin is a marvelous barrier to most microbes, including this one. It’s only where there are openings that the virus can enter.

- Keep a little distance between yourself and others, if you can. Avoid large gatherings. Skip shaking hands, hugs, etc. with acquaintances.

- Don’t get out and about if you don’t need to. If you are sick, stay home. If you have symptoms of the flu or a cold that you wouldn’t normally seek treatment for, don’t seek treatment now. If you are otherwise healthy, don’t go to the ER or your doctor for mild respiratory symptoms. Even if you have COVID-19, remember that it is caused by a virus and there is no curative treatment, anyway. If you get seriously sick, your treatment will consist of supportive care to manage your symptoms until your immune system can overcome the virus.

- Older folks need to stay as isolated from others as possible, because they are in the most danger from the infection. Help them out if you can. For instance, offer to go to the store or the pharmacy for them.

- PLEASE do not react to every piece of information that spews out of your TV, computer or telephone. In time like this, it is of the utmost importance that people have accurate information. Make sure information is true before you share it with others. This is something we should all do, all the time, but it’s especially important now. If you want accurate information, go directly to the US Center for Disease Control www.cdc.gov . There is a link to the latest information relating to the virus and COVID-19 right at the top of the page. You can also go to the Kentucky Department of Public Health. They have a special website just for this. www.kycovid19.ky.gov . Both of these sites are updated constantly with the latest information. We have an exceptionally good Health Department in Hopkins County. Their web page ( www.hopkinscohealthdept.com )and their social media will also have the latest information available. County health departments exist for this very thing. They know what they are doing and they do it well.

This is an unusual time. Pandemics are, thankfully, fairly rare. The word “pandemic”, by the way, refers to the spread of a disease, not its severity. It just means that a contagious disease has spread widely over multiple continents. HIV/AIDS has been a pandemic disease for almost 40 years. The H1/N1 flu of 2009 was a pandemic that killed over a million people, worldwide. There was another flu pandemic in 1968. If we act responsibly and behave in a reasonable, compassionate, and disciplined manner, this one will pass with as little harm as possible.

Electron micrograph of SARS CoV 2 Credit: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease

Artist rendering of SARS CoV 2 Credit: US Centers for Disease Control

Well said.